Neural Discovery in Mathematics: Do Machines Dream of Colored Planes?

Our ICML 2025 Oral Paper Neural Discovery in Mathematics: Do Machines Dream of Colored Planes? introduces a novel neural network approach to tackle the famous Hadwiger-Nelson problem and related geometric coloring challenges. We reformulate the combinatorial task as a continuous optimization problem, enabling neural networks to find probabilistic colorings. This led to discovering two new 6-colorings, marking the first progress in 30 years on a key variant involving different forbidden distances and significantly expanding the known solution range.

The chromatic number of the plane

The Hadwiger-Nelson (HN) problem, first posed in 1950, asks a fundamental question at the intersection of geometry and combinatorics: What is the minimum number of colors needed to color the entire Euclidean plane $\mathbb{R}^2$ such that no two points at unit distance share the same color? This minimum number is referred to as the chromatic number of the plane, denoted $\chi(\mathbb{R}^2)$, as it is the chromatic number of the infinite graph with vertex set $\mathbb{R}^2$ and edges connecting pairs of points at unit distance. What makes this seemingly simple setup challenging is the combination between discrete choices (the colors) with continuous geometry (the distance on the plane).

Despite over 70 years of research, the exact value of $\chi(\mathbb{R}^2)$ remains unknown. It is currently bounded between 5 and 7, i.e., $5 \le \chi(\mathbb{R}^2) \le 7$. Establishing lower bounds typically involves constructing finite unit-distance graphs—graphs with a high chromatic number, that is, graphs that can be embedded in the plane in a way such that edges connect points exactly one unit apart. Notable examples include the Moser spindle, which requires 4 colors

In this work, we focus on improving the upper bounds. We explore how neural networks (NNs) can serve as a tool for mathematical discovery, guiding our intuition towards potential new constructions for this problem and its variants.

A New Approach: Neural Networks for Mathematical Discovery

Modeling the Coloring Problem

We introduce a new approach to generate colorings which avoid unit distance conflicts using NNs. The core idea is to reframe the combinatorial problem as a continuous optimization task that NNs are well-suited to handle. Instead of assigning a fixed color (a discrete choice) to each point, we relax the constraint by defining a probabilistic coloring. We train the NN to output a probability distribution over the available colors for any given point $(x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2$.

Let $p_\theta: \mathbb{R}^2 \to \Delta_c$ be an NN parameterized by $\theta$, where $c$ is the number of colors and $\Delta_c$ is the $c$-dimensional probability simplex. For an input point $x \in \mathbb{R}^2$, the output $p_\theta(x) = (p_1, …, p_c)$ represents the probability distribution over the colors that point $x$ can attain.

We then train the network in an unsupervised way, that is, without labeled data. Instead, we define a way to measure how “bad” a probabilistic coloring is according to the problem’s constraints. The resulting loss function is differentiable thanks to the probabilistic nature of the relaxed problem, allowing us to measure the violation of the unit distance constraint within a finite region $[-R,R]^2$. For the standard Hadwiger-Nelson problem, the loss function calculates the expected probability that two points $x, y$ exactly one unit apart do share the same color when said colors are sampled from their respective distributions $p_\theta(x)$ and $p_\theta(y)$:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \int_{[-R, R]^2} \int_{\partial B_1(x)} p_\theta(x)^T p_\theta(y) \; \mathrm{d}y \; \mathrm{d}x,\]where $\partial B_1(x)$ is the unit circle around $x$.

In practice, we approximate this loss and its gradient using Monte Carlo sampling. At each training step, we sample a batch of $n$ center points $x_i \sim \mathcal{U}([-R, R]^2)$ and for each $x_i$, we sample $m$ points $y_{ij} \sim \mathcal{U}(\partial B_1(x_i))$ from the unit circle around it. The loss for the batch is then approximated by the average conflict probability:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{nm} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{m} p_\theta(x_i)^T p_\theta(y_{ij}).\]The entire setup is differentiable with respect to the network parameters $\theta$, allowing us to use standard gradient descent algorithms (like Adam

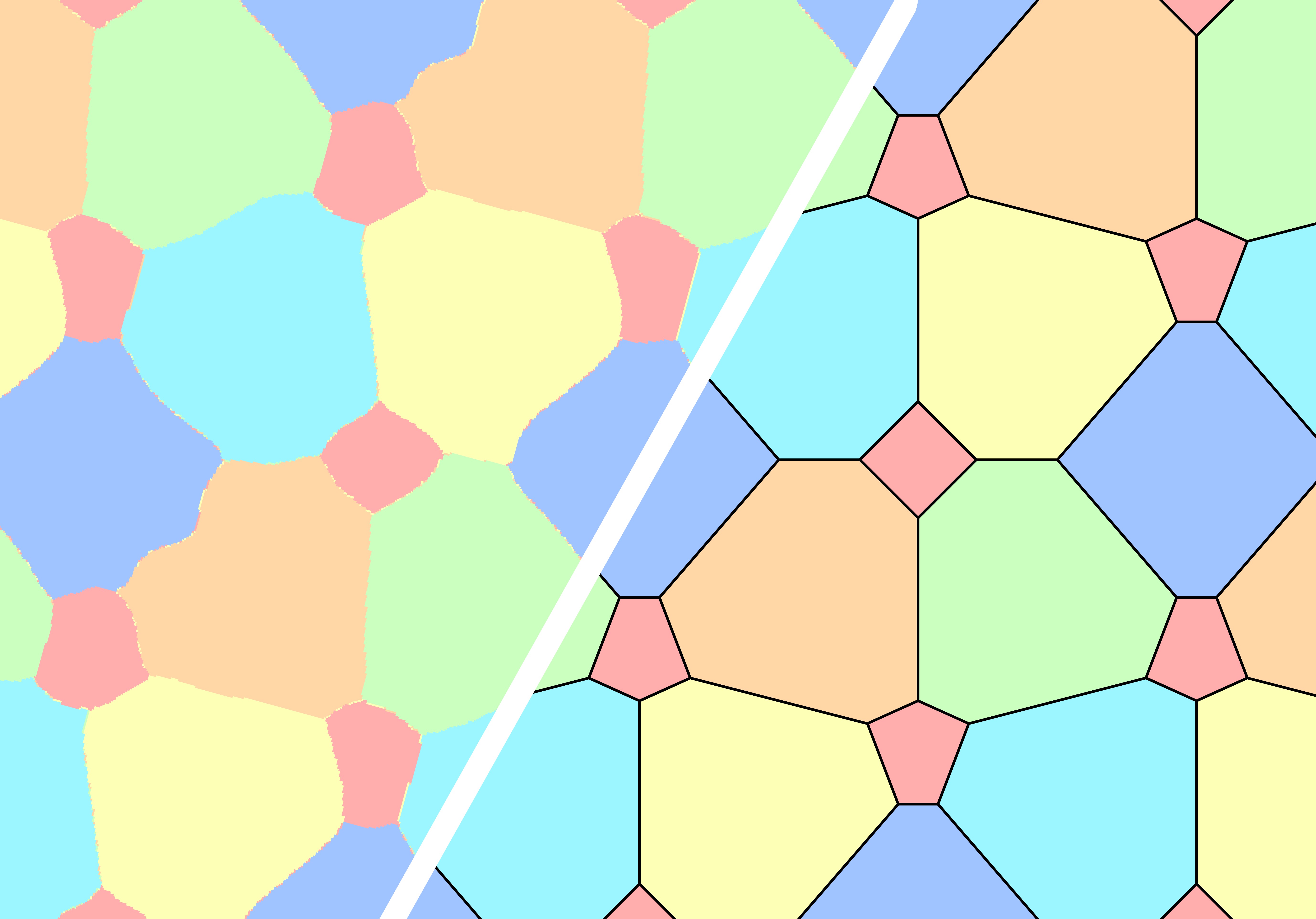

The following animation illustrates this learning process, showing how the initially random probabilistic coloring evolves over training iterations to form a structured pattern that minimizes conflicts. We depict $\text{argmax}\ p_\theta(x)$, i.e., for each pixel we choose the color which currently has the highest probability.

Guiding Mathematical Intuition

The NN acts as a powerful function approximator, capable of learning complex spatial patterns directly from the geometric constraints, largely without strong built-in assumptions about symmetry or periodicity. Crucially, we use this approach not to find fully automated proofs, but as a tool to guide mathematical intuition

Coloring Variants and Recent Progress

While finding a 6-coloring for the original problem remains difficult (our NNs consistently find patterns needing seven colors, aligning with the possibility that $\chi(\mathbb{R}^2)=7$), this NN-based optimization approach proved highly successful on related variants of the problem.

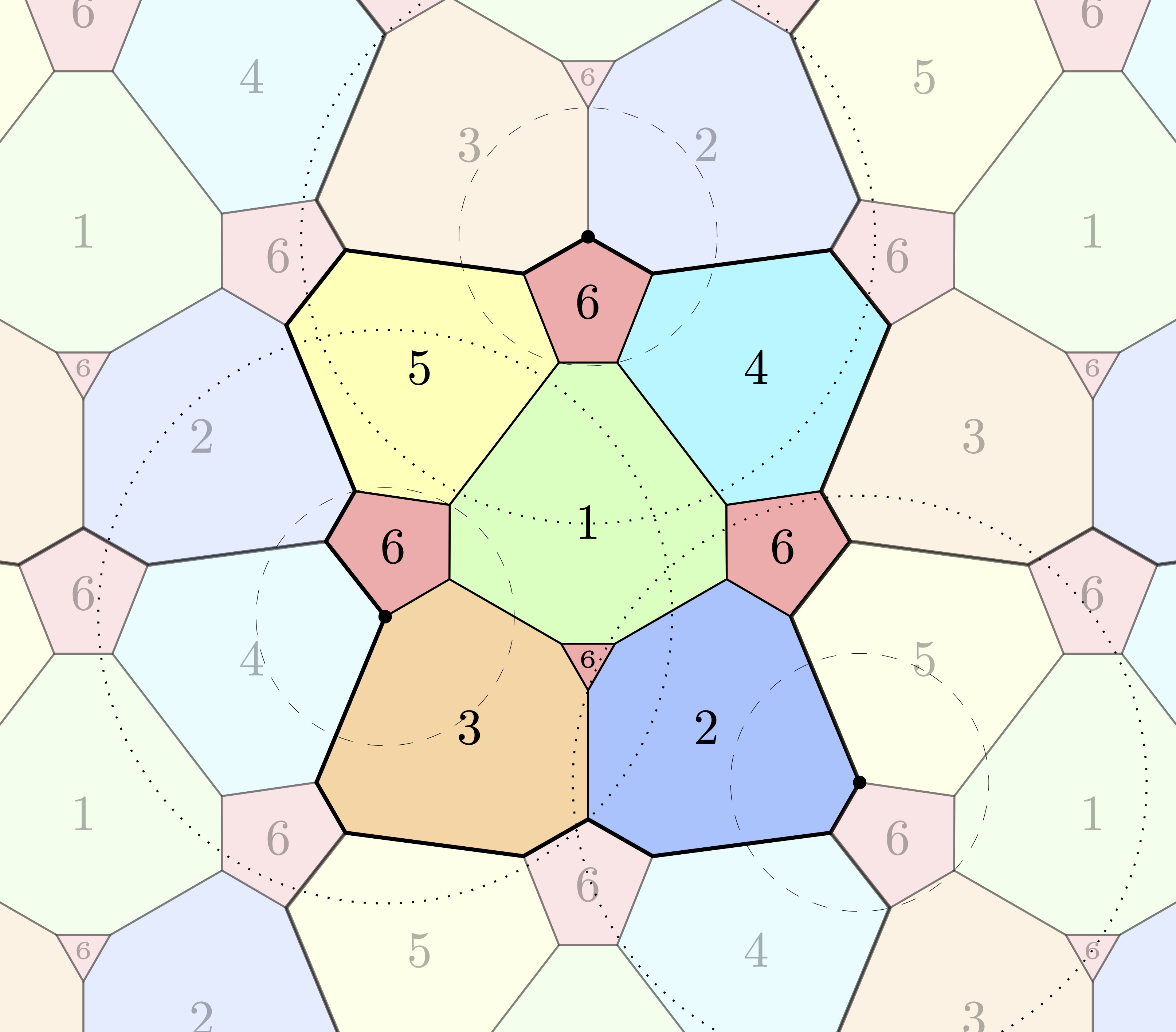

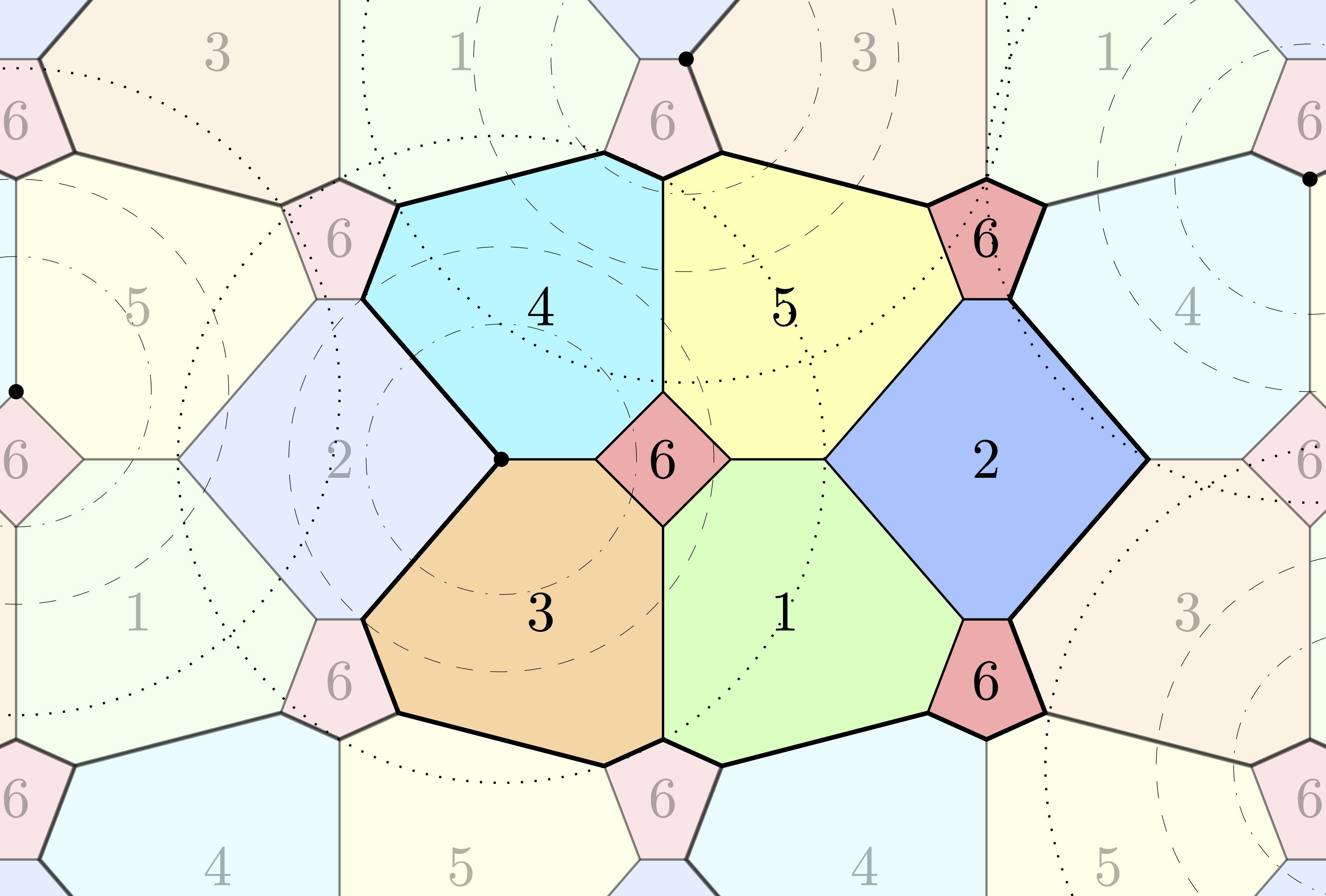

A key variant we studied is the $(1,1,1,1,1,d)$ coloring problem: coloring the plane with six colors s.t. pairs of points assigned the first five colors must avoid unit distance, while pairs assigned the sixth color must avoid a different distance $d > 0$. Prior to our work, such colorings were only known to exist for $d \in [\sqrt{2}-1, 1/\sqrt{5}] \approx [0.414, 0.447]$

To tackle this variant, we modify the loss calculation. Instead of penalizing only unit-distance conflicts for all colors, the loss sums the conflict probabilities for each color $k$ with its specific forbidden distance $d_k$. In the sampling approximation, for a batch of points $x_i$, we sample points $y_{ij}^{(k)}$ at distance $d_k$ from $x_i$ for each color $k$, and the loss becomes:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{nm} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{m} \sum_{k=1}^6 p_\theta(x_i)_k \cdot p_\theta(y_{ij}^{(k)})_k\]where $d_1=…=d_5=1$ and $d_6=d$. This loss penalizes pairs $(x_i, y_{ij}^{(k)})$ having the same color $k$ if their distance is the forbidden distance $d_k$.

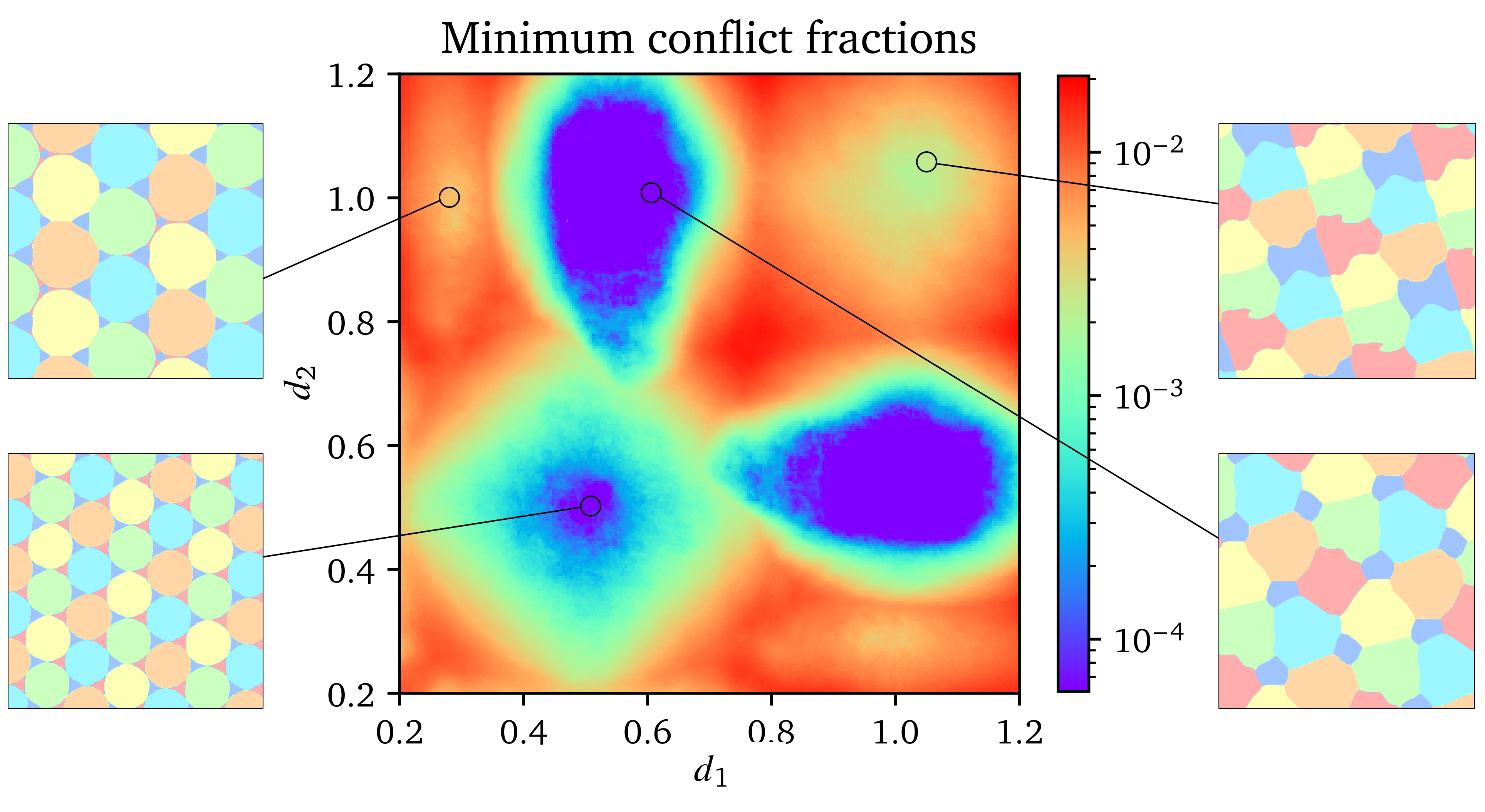

We also explored other variants, such as the $(1,1,1,1,d_1,d_2)$ problem, where two colors have distinct forbidden distances $d_1$ and $d_2$. Our framework easily adapts by modifying the loss calculation to incorporate the specific distance constraints for each color pair. The figure below shows a heatmap of the minimum conflict rate found by the NN for the $(1,1,1,1,d_1,d_2)$ variant across different values of $d_1$ and $d_2$.

Focusing on the $(1,1,1,1,1,d)$ variant, our NN approach, exploring different values of $d$, discovered patterns that guided us to formally construct and verify two new families of 6-colorings. These constructions were published in a specialized venue

Together, these NN-inspired constructions significantly expand the known continuum of realizable distances $d$ to $[0.354, 0.657]$, representing the first progress on this problem variant in 30 years.

Note that the distance $d$ in the last color introduces an additional degree of freedom. While it would be possible to just run our approach for many values of $d$, we realized that we can parametrize whole families of colorings by including the distance $d$ in the input of the NN. Querying then network at $(x, d)$ then yields the probability distribution over the colors at point $x$ if the forbidden distance in the last color is $d$. To visualize the exploration process for the $(1,1,1,1,1,d)$ variant, the following animation shows how the probabilistic 6-coloring found by the NN (left) and its corresponding conflicts (right, where black points indicate violations) change as the forbidden distance $d$ for the sixth color varies:

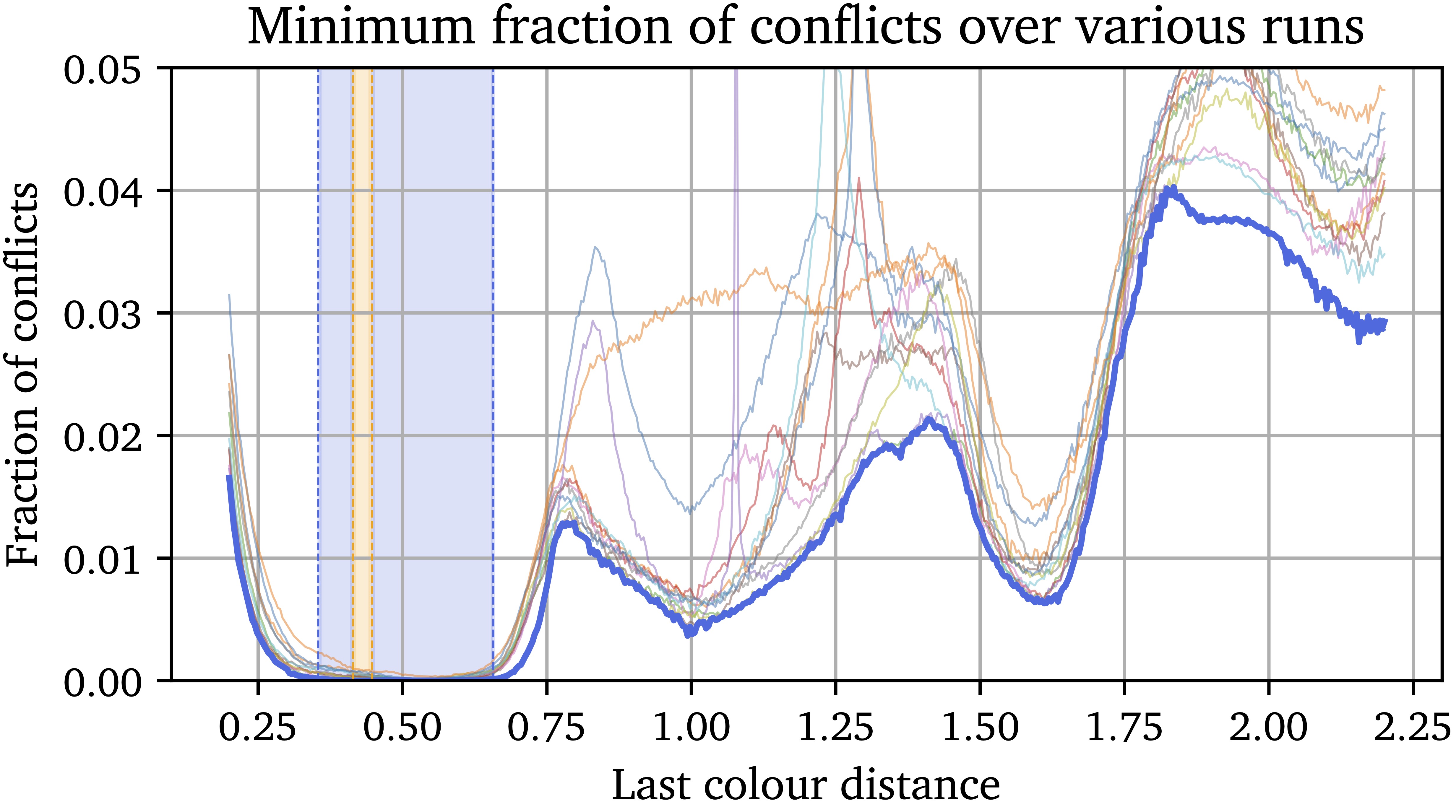

The plot below further summarizes these findings by showing the minimum conflict rate achieved by the NNs across different distances $d$. Lower conflict rates suggest that a valid formal coloring might exist for that $d$. The blue region highlights the significantly expanded range of $d$ where our new constructions provide valid 6-colorings, compared to the previously known range shown in orange.

Almost Coloring the Plane

Beyond the distance variant, our framework demonstrated its applicability to other related geometric coloring problems, such as “almost coloring” the plane, arising as a natural extension of the HN problem: what is the minimum fraction of the plane that must be removed such that the remaining points can be colored with $c$ colors without monochromatic unit-distance pairs? We introduced an additional $(c+1)$-th color, corresponding to the removed points, and used a Lagrangian relaxation approach. This involves a modified loss function that penalizes conflicts among the first $c$ colors while also penalizing the use of the $(c+1)$-th “uncolored” color via a Lagrange multiplier $\lambda$.

Our numerical experiments for $c=6$ colors recovered patterns resembling known constructions involving intersecting pentagonal rods

| # Colors ($c$) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best known density removed | 77.04% | 54.13% | 31.20% | 8.25% | 4.01% | 0.02% |

| Our results (approx. density removed) | 77.07% | 54.21% | 31.34% | 8.29% | 3.60% | 0.03% |

Conclusion and Outlook

Our work highlights the potential of NNs as tools for mathematical exploration. By reformulating combinatorial geometry problems, like the Hadwiger-Nelson problem and its variants, as continuous optimization tasks, we can experimentally discover new and potentially interesting patterns. While these networks do not yield formal proofs directly, they effectively explore complex solution spaces and uncover structured patterns that can guide mathematical intuition.

The discovery of two novel 6-colorings for the $(1,1,1,1,1,d)$ distance variant, significantly extending the known range of valid distances $d$ and marking the first progress in three decades, serves as a strong testament to this approach’s potential. It demonstrates how gradient-based optimization on continuous relaxations in combination with the powerful approximation capabilities of NNs can uncover combinatorial structures that have long eluded traditional methods, offering a promising new paradigm for tackling longstanding open problems in discrete mathematics and theoretical computer science.

If you find this interesting and if this work is helpful for your research, please consider citing our paper:

@inproceedings{mundinger2025neural,

title={Neural Discovery in Mathematics: Do Machines Dream of Colored Planes?},

author={Mundinger, Konrad and Zimmer, Max and Kiem, Aldo and Spiegel, Christoph and Pokutta, Sebastian},

booktitle={Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning},

year={2025},

url={https://openreview.net/forum?id=7Tp9zjP9At},

}